What is Life?

by Blaise Agüera y Arcas

I read the book “What is Life? Evolution as Computation” by Blaise Agüera y Arcas, one of the co-authors of the computational life paper that we recently analyzed. The book is cool, more popular than scientific, quite heavily built around the results of that very article, and here the author allows himself to reason much more broadly in different directions.

The book itself is in turn part of an even broader book “What is Intelligence”. Matryoshkas are everywhere. What’s nice is that the latter book is available in open access and “What is Life” can be read there as the first chapter.

Life and Computation

Overall, the book focuses on the question of the connection between life and computation, and it starts from afar, with abiogenesis, as well as the reverse Krebs cycle, which could synthesize the first necessary organics. Next, the author moves to symbiogenesis, which gives evolution a much broader field of action than basic mutations—they can fine-tune, optimize, and add diversity, but symbiogenesis opens new combinatorial spaces and brings revolutionary change to evolution.

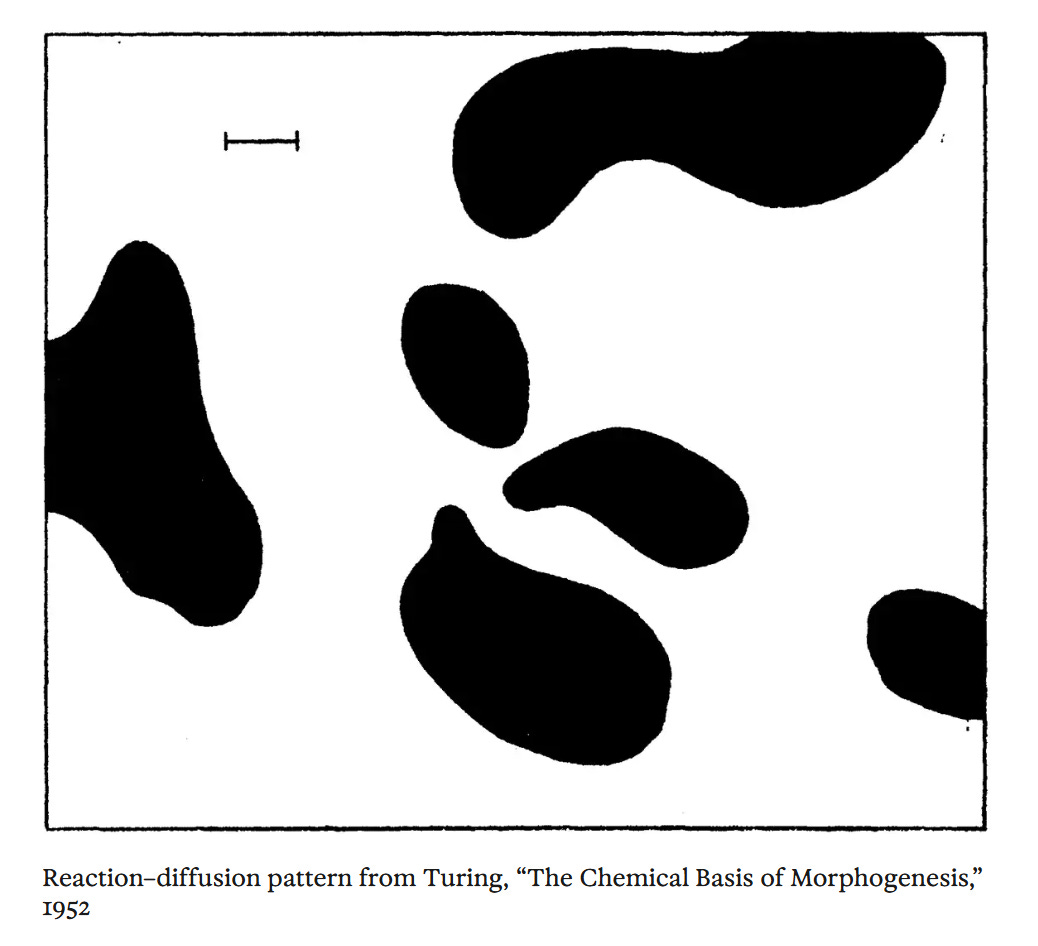

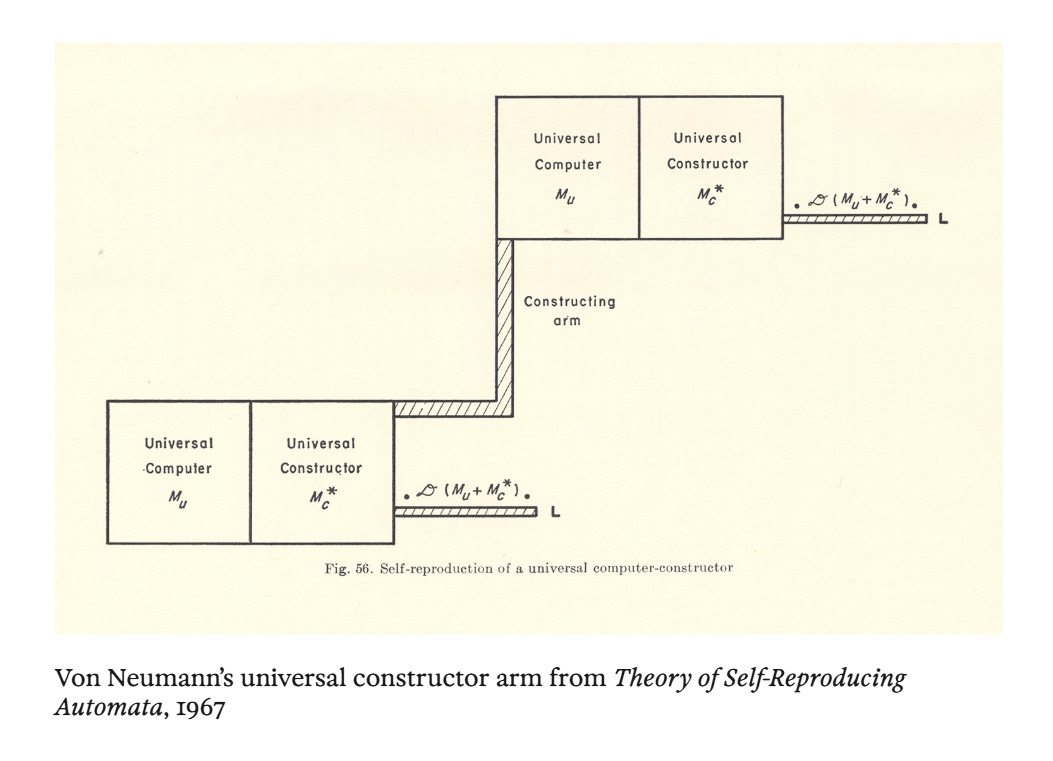

In the author’s opinion, computer science occupies a significant place in understanding life. Both Turing and von Neumann initially saw many parallels between computers and brains, and by the end of their lives both came even closer to biology—morphogenesis and reaction-diffusion patterns for Turing, and self-replicating automata and the universal constructor for von Neumann. An interesting fact I didn’t know—that Turing insisted on including an instruction for random numbers in the Ferranti Mark I computer. To von Neumann, of course, we owe among other things the architecture of modern computers named after him.

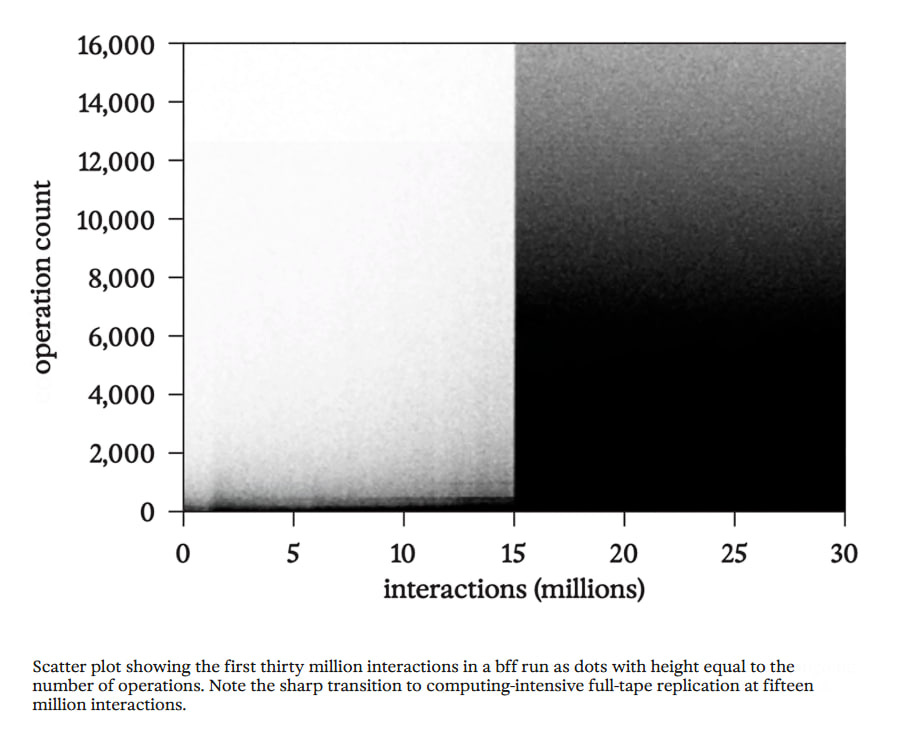

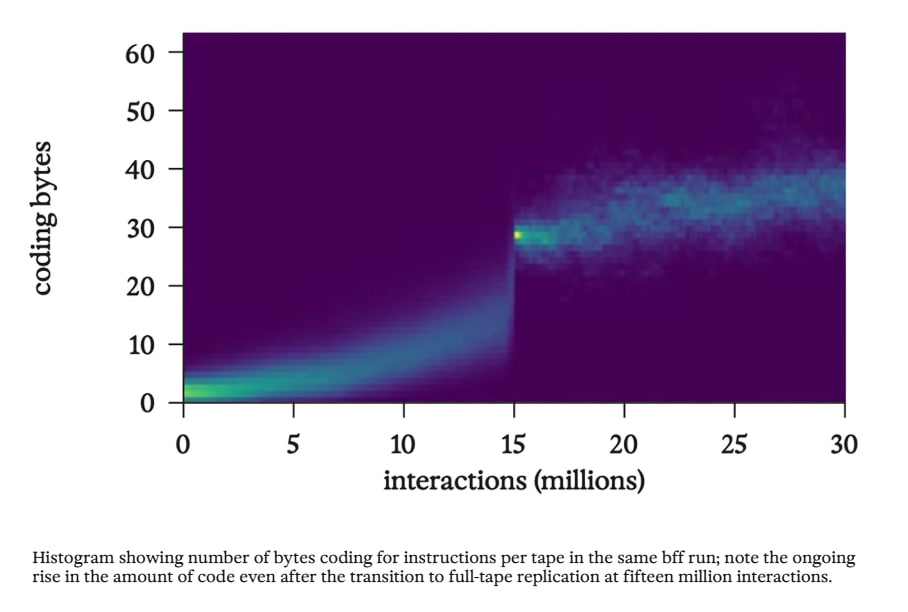

The chapter on Artificial Life tells about the results of that article with Brainfuck (bff). There are new pictures here that weren’t in the original article: about the jump-like growth in the number of computations and about the number of encoding bytes on the tape.

Thermodynamics, which for a long time was a purely practical discipline, didn’t immediately receive a scientific apparatus describing and explaining the operation of heat engines. Modern AI seems to be in a similar situation. For studying artificial life, bff is possibly a suitable model object, analogous to billiard balls serving as a model for molecular collisions in an ideal gas. About billiard balls, by the way, a cool article came out recently, I’ve just dropped an auto-review.

Why does complexification occur in the environment? This sort of violates the second law of thermodynamics. Replicators arise in bff because an entity that reproduces is more dynamically stable. A passive object, no matter how strong it is, is fragile, while a reproduced pattern is anti-fragile. As long as DNA or something else can replicate, the pattern is eternal. Darwinian selection in thermodynamic terms is equivalent to the Second Law, if we consider populations of replicators—a more efficient replicator is more stable than a less efficient one. The unification of thermodynamics with computation theory can help understand life as a predictable outcome of a statistical process. In our model environment, if computations are possible, then replicators will be a dynamic attractor, because they are more dynamically stable.

Symbiogenesis leads to the complexification of replicators. In the article, the replicator assembled from simpler code pieces as a result of symbiotic events. Judging by the graphs, an exponential takeoff occurred in the soup. With the appearance of a true replicator comes substantial progress in evolvability. Now everything that doesn’t break the copying code is inherited, and classical Darwinian selection has the opportunity to launch.

Early replicators were most likely unable to perfectly copy everything, and copied only small pieces of code, inserting them anywhere. This was a chaotic phase, when everything still looks like random, but the number of computations begins to grow. In the article there was also a stage of poisoning the soup with zeros due to low-quality replicators. Poor replicators compete with each other, and also participate in symbiotic events. Tracing the origin of individual bytes in the soup can help see what’s happening in it. There’s a cool new video here about the origin of individual bytes in the ecosystem:

Provenance of individual bytes on tapes in a bff soup after 10,000, 500,000, 1.5 million, 2.5 million, 3.5 million, 6 million, 7 million, and 10 million interactions. The increasing role of self-modification in generating novelty is evident, culminating in the emergence (just before 6 million interactions) of a full-tape replicator whose parts are modified copies of a shorter imperfect replicator.

The chaotic phase is a potential cauldron for launching directed evolution and doesn’t last long. The exponential launches and a soup takeover occurs. In this chapter of the book there are some reflections about the toy bff universe and how this potentially transfers to life on Earth or other planets.

Interesting conclusions from bff:

Symbiogenesis is more important than random mutations.

Complex replicating things arise after simple ones.

Sub-replicators inside replicators allow us to glimpse the past.

The first true replicator is an “event horizon” destroying traces of imperfect replicators that existed before it.

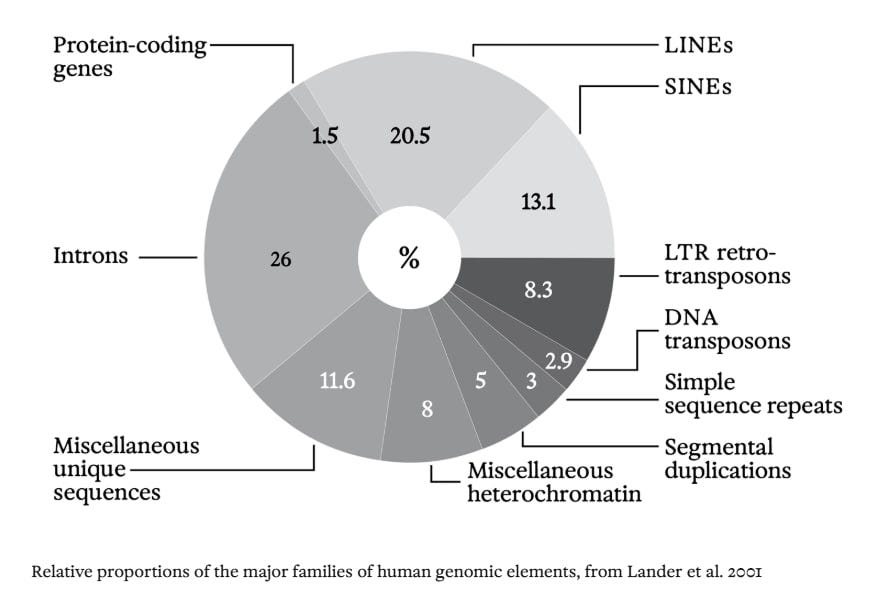

Evolved code must not only contain instructions for its replication, but also be filled with subsequences containing instructions for independent self-replication.

If symbiosis between these parts created novelty driving evolution as a whole, we should see in the genome traces of many broken or incomplete sub-replicators.

Code evolved through such hierarchical symbiotic replication must contain many repeating sequences or copies of other parts.

All this nicely resonates with the viral world and the presence in our DNA of a huge number of mobile elements, transposons, and viral DNA. We also have a bunch of sub-replicators inside the genome.

This entire structure with nested self-replicators somewhat resembles a fractal or rather a multifractal. When the soup transitions to replicating full tapes, the compressibility of the tapes increases.

Compositionality, hierarchy, and recursion exist both at the genome level and the body level. We don’t have separate genes for each of our ribs; the construction of a rib is analogous to a “procedure/function” in a programming language and this code is reused many times. In this sense, life is quite computational, evolution creates real programs that reuse code.

Ultimately, the author proposes his definition of life:

Life is self-modifying computronium arising from selection for dynamic stability; it evolves through the symbiotic composition of simpler dynamically stable entities.

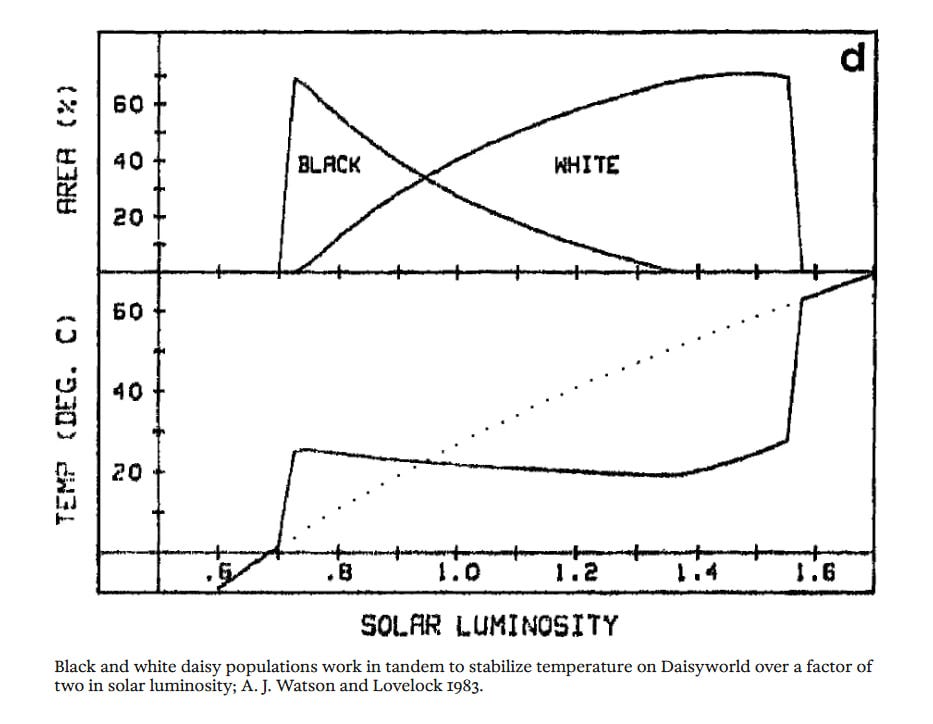

Computronium here is a state of matter, which in turn can be anything supporting computations: bytes in bff, pixels in a cellular automaton. A planet (a model one like Daisyworld or a real one like Earth), from his point of view are also alive. Technologies we create can also fit into this definition and be part of the picture of life.

In general, a curious little book, there’s something to think about. I’ll be reading the broader “What is Intelligence?” next.

And here’s a three-month-old video with the author, in which he touches on the same theme about life very extensively:

See also a recent MLST talk: